It takes passion to dedicate your life to a species most people never think about, to fight seemingly impossible battles, and to keep hope alive when the odds are against you.

In those early days, I followed wild orangutans, learning their ways, observing their behavior. They are the true indigenous inhabitants of Borneo.

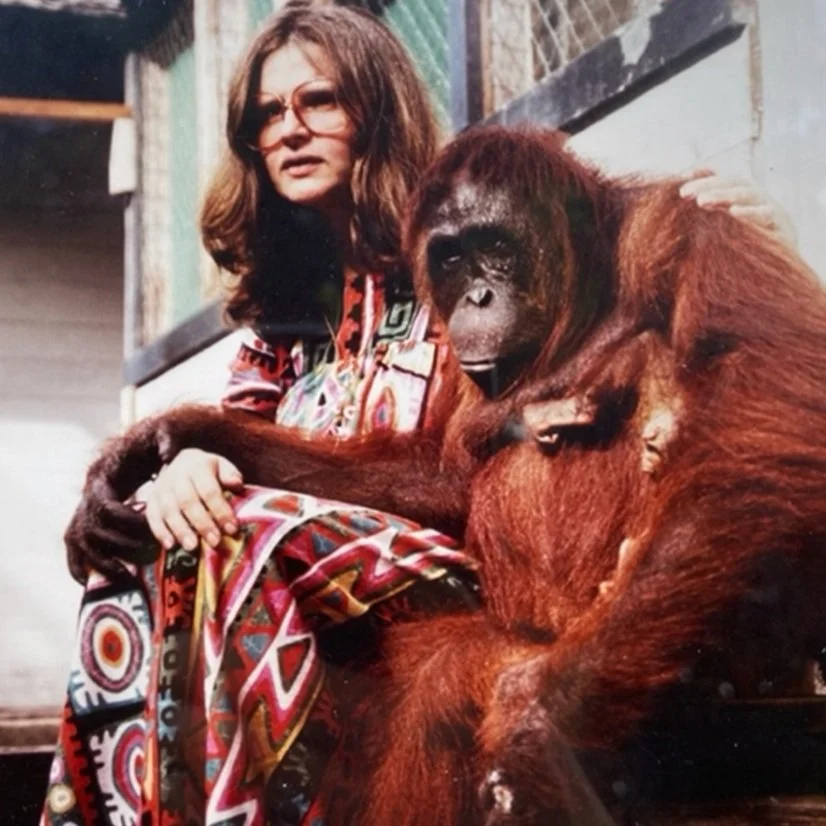

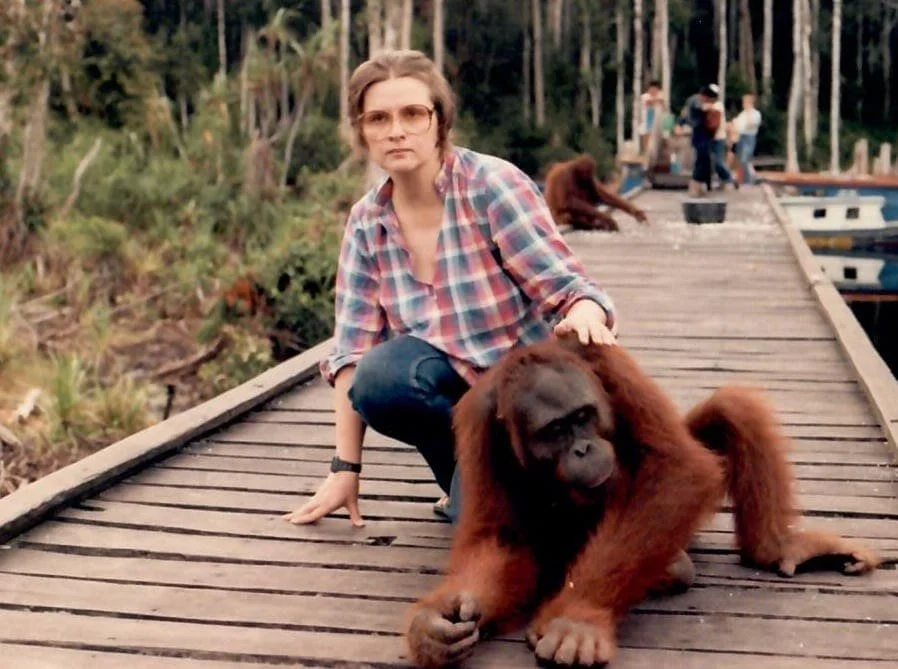

Dr. Biruté Mary Galdikas

When I first arrived in Borneo in 1971, it was a different world. I came to study wild orangutans, but what I found was a forest under siege: illegal loggers, hunters, and all manner of threats to the natural world. The orangutans had no sanctuary, no one to speak for them. So, I set up Camp Leakey on the banks of the Sekonyer River. It was a modest beginning, but it became the heart of my work and the foundation for everything that followed.

In those early days, I followed wild orangutans, learning their ways, observing their behavior. They are the true indigenous inhabitants of Borneo. They have lived here for thousands, perhaps millions, of years. And yet, we humans, colonizers in every sense of the word, have invaded their world, taken their land, and pushed them to the brink. I saw the destruction creeping closer year by year and I realized that if I didn’t do something, no one would.

Photo by OFI

And so orangutans have been my life’s work, my passion. It takes passion to dedicate your life to a species most people never think about, to fight seemingly impossible battles, and to keep hope alive when the odds are against you.

In the early days, I was like a mother to the wild-born ex-captives, sleeping in a hammock with them, caring for them, and watching them grow. But orangutans don’t stay young forever. The ones I raised in the 1970s and '80s are mostly gone now. Today, I’m following their daughters, granddaughters, and even great-granddaughters. These new generations are proof that our rehabilitation efforts worked. Many live as if they were never captive, spending months in the forest, foraging and thriving on their own.

My relationship with them is more distant now. The days of infants in my hammock are behind me. Now my role is to observe, document, and understand how these new generations live and adapt. It’s a different connection, but no less meaningful.

Photo by OFI

It’s in the Eyes

Orangutans aren’t our brothers and sisters - that title belongs to the African great apes: chimpanzees, gorillas and bonobos, who are more closely related to us. Orangutans are our aunts and uncles. They didn’t leave the trees when our ancestors did. They stayed in the Garden of Eden, adapting to the rainforests that have been their home for millions of years.

But I’ve always believed orangutans are more than just distant relatives. They’re our mirror. When we look into their eyes, we see something ancient, something timeless, something that reflects who we once were. They’re a living link to our early hominid ancestors, a bridge to a past we’ve long forgotten. I think that’s why people find them so mesmerizing. They may not be able to explain it, but they feel a deep, unspoken recognition.

Photo by OFI

If you ever meet an orangutan, I promise, it will change your life. It reminds you of the beauty and fragility of this world, and of our responsibility to protect it. I’ve come to think of looking into an orangutan’s eyes as a “wormhole to god”: you see something profound, a mirror to your own soul, a glimpse of the divine. People rarely describe feeling the same when looking into a chimpanzee’s eyes. Gorillas, maybe. But with orangutans, it’s almost universal. Their gaze is hypnotic, humbling, transformative. It cuts through the noise and reminds us what truly matters.

Photo by OFI

There’s one moment I’ll never forget. Years ago, a young banker visited Camp Leakey. She met Tom, a sub-adult male on his way to becoming an adult. She reached out, took his hands, and they gazed into each other’s eyes. Something passed between them, beyond words. When she returned to Chicago, she quit her job, ended her engagement to her fiancée, another banker, and went to veterinary school. All because of that moment with Tom. That young woman found her purpose from a single moment. And she’s not the only one. Time and again, I’ve seen it: volunteers, visitors, researchers. They come to Camp Leakey, and their lives are forever changed.

Photo by David Metcalf

These moments remind us of our place in the natural world, and our duty to protect it. Camp Leakey has always been a place where those connections happen. Visitors used to casually encounter adult male orangutans on the trails, like they were passing an old friend, and a visitor once said, “If these were chimpanzees, everyone here would be dead.” It’s true, orangutans are different - they have a calmness and a gentleness that invites connection.

Of course, those experiences are rarer now. We wouldn’t allow that kind of physical contact today since disease transmission is a real risk. But the spirit of Camp Leakey remains. It’s still a place where people come to understand not just orangutans, but themselves.

Photo by OFI

Connection to god

I’ve come to see that Nature is god. No matter your faith - or lack of one - nature is the beginning and the end. Spiritual traditions may guide us, but ultimately, they lead us back to the natural world. That’s where meaning lives.

In our modern world, we’ve grown so disconnected from nature. We’ve forgotten what it feels like to stand in a forest, hear its quiet wisdom, see the sun through the canopy, feel life all around us.

I once heard Al Gore say, “The environmental crisis is a spiritual crisis.” He’s right. The connection people feel with orangutans is not just emotional, it’s spiritual. I believe that spiritual bond holds the key to saving orangutans, the planet, even ourselves. We need to reconnect with nature, to feel its beauty, its power, and let it move us to act.

If we can rekindle that connection, especially in our leaders, real change might be possible. I find hope in small moments, like watching the President of Indonesia gently holding his cat. That tenderness, that bond with life, is what we need to nurture in everyone.

Photo by David Metcalf

You can find it standing under an ancient oak tree, walking through a quiet forest, or listening to the sound of a river. In Japan, they call it ‘forest bathing’: the practice of immersing yourself in nature to heal your body and soul. These quiet moments, when we step away from our screens and truly engage with the natural world, are where healing begins. Nature has a way of speaking to us, if we’re willing to listen. I hope everyone who reads this takes a moment to reflect on their own connection to nature, wherever they are.

In the end, it’s not about what we accumulate or achieve, but the relationships we build, with our families, each other, and the natural world. Those connections are what sustain us. They give life meaning. So go outside. Look at a tree. Feel the wind on your face. And remember: nature is god. And we are its stewards.

Photo by David Metcalf

Education & Storytelling

I’ve always believed that the key to saving orangutans, and any species, is education. If people don’t understand these animals, if they don’t see their intelligence, emotions, and value, then why would they protect them? That’s why I’ve always encouraged tourism, telling people, “If you want to save the great apes - chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, orangutans - go to their habitat countries. Visit their forests. Support local economies.”

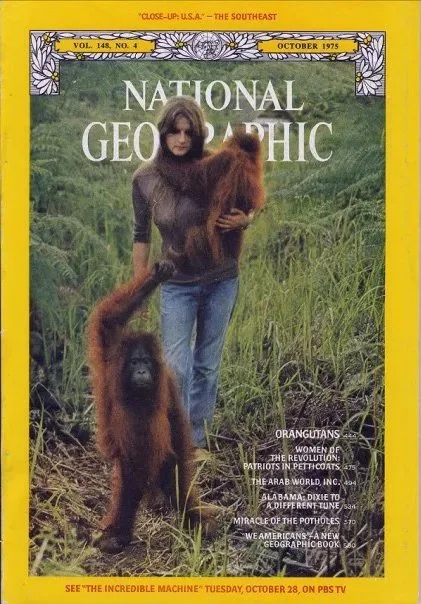

When I arrived in 1971, not a single tourist came to Tanjung Puting. By 1975, we began encouraging visitors. Today, it’s one of the top tourist destinations in Indonesian Borneo. Tourism has brought awareness, funding, and jobs for local people. It’s made a real difference, not just for orangutans, but for the entire ecosystem.

Photo by David Metcalf

When I first started talking about orangutans as our relatives, saying that they were our brothers and sisters, the idea was met with ridicule. But as we’ve learned more about their genetics and behavior, perspectives have shifted. People now understand orangutans are part of our family tree, even if they branched off millions of years ago. That change in perspective has been one of the most rewarding parts of my work.

When I lived full-time at Camp Leakey, I gave talks to every group of Indonesian visitors who came through. I spoke at schools, village gatherings, and to anyone who would listen. I told them about orangutans’ intelligence, their emotions, and their role in the forest. I reminded them that the forest isn’t just the orangutans’ home, it’s ours too.

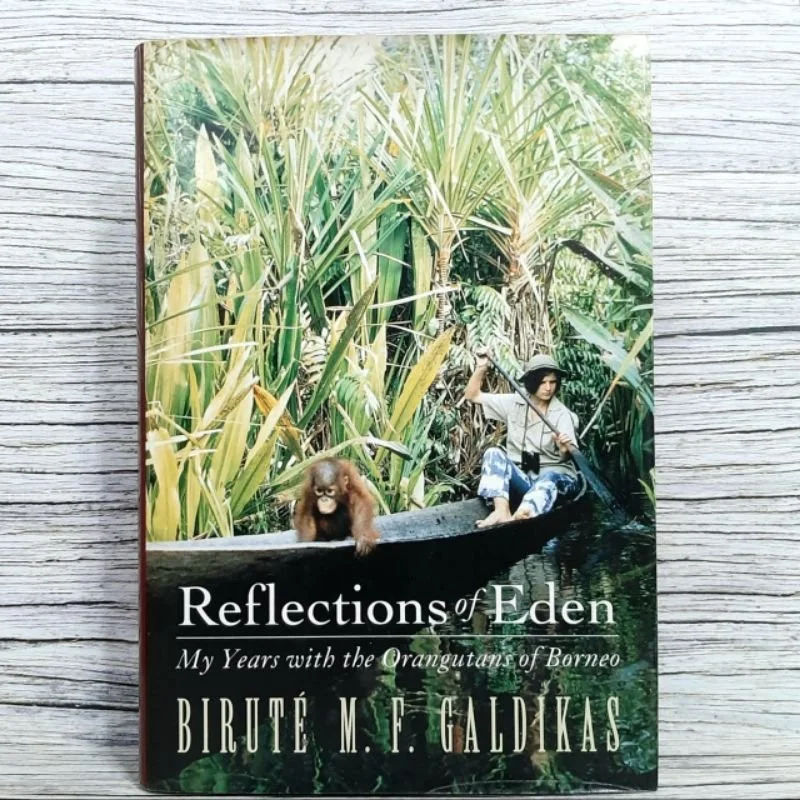

Cover by National Geographic

Over the years, I’ve seen education change minds and hearts. Local people who once saw orangutans as pests now see them as part of their heritage. Children who grew up hearing my talks have become conservation advocates. It’s a slow process, but it’s real.

I’ve learned that stories can move people in ways statistics never will. It's not enough to explain why orangutans are endangered or show a picture of an orangutan. We have to show why orangutans matter, explain what orangutans mean to our own origins, and who orangutans represent.

An Australian filmmaker once told me, “People don’t care about animals. They care about the people who work with animals.” He wasn’t wrong. Films about Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey have done more to change public attitudes toward great apes than any report ever could. Years ago, after a short documentary about my work aired in Australia, thousands of dollars poured in, small donations, $5 and $10 at a time. That support wasn’t just for the orangutans. It was for the story behind them.

That’s why storytelling lies at the heart of conservation. We need people to see that these beings, these forests, these ecosystems are worth saving - and we have to make it personal, because when people feel connected, they act.

Photo by OFI

Palm Oil

I’ve spent years educating the palm oil industry on the importance of conservation, speaking to executives, leading training sessions, and even helping managers give presentations to local schools. Some of them get it. They’ve stopped killing orangutans, and when one is found on their plantations, they contact us or the forestry department to help relocate the orangutan. That’s progress. But it’s not enough.

Photo by OFI

At one meeting, I proposed expanding the buffer zones around rivers in plantations from 500 meters to a kilometer, to preserve more native vegetation. Do you know what happened? They laughed. Not out of malice, but because the idea seemed unthinkable. “We wouldn’t make a profit,” they said.

One of the most surprising things I’ve learned is that when you meet the so-called ‘enemy’ face to face, they’re often just human. The managers I worked with weren’t villains. They were intelligent, curious people who wanted to learn. Many genuinely cared about orangutans, but they were trapped in a system that prioritizes profit above all else.

Photo by David Metcalf

Despite the victories, the destruction of the rainforest continues, palm oil plantations are still expanding, and the profits they generate often outweigh any ethical considerations. That’s the reality we’re up against. The world is driven by profit, and until that changes, the destruction will continue.

But I don’t give up. I keep talking and educating, because every small victory matters. As I told one group of palm oil managers, the handwriting is on the wall. The question is whether we’re willing to read it, and act, before it’s too late.

Photo by David Metcalf

Road to Extinction

There’s still so much we don’t know about orangutans, even after all these years. I asked Ruth, one of my PhD students to help me do a genetic survey of my study population as I had documented over the decades a very clear change in the structure of the population. The numerous transient adult males were gone; they were no longer passing through the study area as they had in the past. The 1990s and early 2000s were a constant whirlwind of crises in the park, and long-term studies often had to wait.

Ruth spent six months collecting data, and what she found was both fascinating and troubling. The males she identified weren’t newcomers from other regions of Borneo, as they should have been, but rather locals, from the park’s periphery. Where were the males from West or East Borneo? Why weren’t they coming into Tanjung Puting anymore?

The answer was heartbreakingly clear: they can’t get through. The forests beyond the park are fragmented, cut off by sprawling palm oil plantations, timber estates, and other development. The corridors that once allowed males to roam and bring genetic diversity have been severed. This is why I’ve long advocated for creating corridors, to reconnect isolated forest patches and restore the natural flow of genes.

Photo by David Metcalf

Ruth’s genetic studies also confirmed what I had long suspected: the females in Tanjung Puting are becoming dangerously inbred. Many were as closely related as first or second cousins. And what does that mean? Inbreeding doesn’t guarantee extinction, but it opens the door to it. It weakens populations, making them more vulnerable to disease, behavioral shifts, even physical changes.

For all the progress we’ve made, the future for orangutans worries me. People think orangutans are thriving because they see relatively many orangutans in forest or at rehabilitation centers, but that’s an illusion. Orangutans live long lives, females can reach 50 or more, so the full impact of habitat loss won’t be visible for decades. By then, it may be too late.

Photo by David Metcalf

In 54 years of following wild orangutans, I’ve seen subtle but significant shifts in their behavior, demographics, and even genetics. Without decisive action, orangutans will slide toward extinction. The forest is their only home, and without it, they cannot survive. Yet the destruction continues, often hidden from view.

I think about the passenger pigeon, how people once watched the skies darken with millions of them, never imagining they could vanish. And then, they were gone. It’s the same with orangutans. We are staring extinction in the face. We just don't see it.

Photo by David Metcalf

Progress, Resilience & Hope

Last year we planted 152,000 trees, only to lose nearly all of them to devastating fires. Fighting those fires was like battling a phoenix, with flames rising again and again from underground peat, reappearing hundreds of meters away.

But we keep planting, because rewilding is just as vital as protecting what remains. Forests are the lifeline to the future. If we lose them, we lose everything. That's why I tell people to plant native trees, patrol the land, protect forests. This isn’t just about saving orangutans, it’s about saving ourselves. The forest is life, and when we destroy it, we destroy a part of ourselves.

The real measure of success is whether the message has been heard, so while I sometimes marvel at how far we’ve come, I also ask myself, ‘have things really changed’? Scientists have been warning for decades: if we don’t change, we’re all in trouble. I wrote about this nearly 30 years ago in Reflections of Eden, when I still believed the Garden of Eden could be found in places like Tanjung Puting. But even then, I knew it was slipping away.

Still, part of my mission, then and now, has been to fight for what remains. To save the last pieces of paradise. As I near the end of my journey, my message remains the same:

We must save the forests so the forests can save us. Profit and convenience have already taken too much. It’s time to give back.

We need to demand better from those in power. We need systemic change. Governments must step up and enforce policies that protect the rainforest. Companies must put sustainability before profit. As long as the world runs on a profit-driven system, progress will remain painfully slow.

We, as individuals, must push for action while making better choices in our daily lives. Stop consuming so much. Eat less meat. Use less palm oil.

And to those planting trees, educating children, or telling stories: I see you, and I thank you. Every step matters. If we can combine a spiritual connection with real political change, maybe, just maybe, we’ll save what remains of Eden.

Photo by David Metcalf

It’s the little stories of hope that remind me that all is not lost: a species believed extinct reappearing in the wild, a new population discovered, or even a small victory in forest restoration. I agree with my friend Jane Goodall: without hope, there is no action. I’ve spent decades spreading that message, from schoolchildren in remote villages to high-level government officials.

I’m proud of what we’ve built. Our education programs have reached thousands of children, inspiring a new generation to protect the forests. We’ve planted nearly a million trees, and we’ve forged lasting relationships, with local communities, governments, and the orangutans themselves, that reflect our deep, enduring commitment. It’s about proving that change is possible, even against overwhelming odds.

Photo by The Explorers Club / Patricia Koo

(Celebrating Dr. Biruté Mary Galdikas and her momentous achievement — recipient of the 2025 Explorers Club Medal)

Orangutans have taught me resilience, patience, and the deep interconnectedness of life. That’s why I keep fighting: through education, research, and advocacy, telling a story of struggle, connection, and survival. As long as there’s a single tree left standing, a single orangutan looking back at us, there is hope. And that hope is worth fighting for.

Photo by David Metcalf